Here are some of my recent essays to nourish the wild soul.

The Values of Soul: #2 Repetition ©Francis Weller

Our exploration of soul values began with the often-neglected practice of restraint. We now venture into another underappreciated quality of soul, and that is repetition. Like restraint, repetition is not glamorous or sexy. It is ordinary and ebbs and flows through our daily lives in both conscious and unconscious ways.

We struggle with the idea of repetition, anything that seems too familiar in this culture. We want things to be novel, new and improved, the latest. There’s nothing wrong with this. It does, however, tinge the old and traditional with a feeling of being antiquated and outdated. (It’s interesting to note that to many traditional people, anything new was approached with an attitude of suspicion. Where did this come from? Will it serve the people? How will it affect the land?)

We live in a society that prizes constant innovation and novelty. The singular focus on growth and development has provided us with many new devices and technologies, and granted us a degree of ease seldom known by our ancestors. It also casts a long and weighty shadow. Embedded in this ideology is an obsession with progress.

Progress is holy scripture in this culture. It is the one-directional arrow of time and productivity that surrounds us and informs us daily. We feel it in the constant pressure to have more, be more, achieve more. There is something inherent in the concept of progress, however, that leaves a residue of discontent in its wake. The better life is always just beyond the horizon, awaiting the arrival of the latest product, accomplishment or discovery. We are taught to crave what’s next, the up and coming. The old and familiar are considered outworn and outdated. We are quick to discard anything considered old—including people—leaving us skimming the surface carried along on the swift moving current of progress.

This pressure is felt in our psychological lives as well. There is an ongoing focus on improving and being better. How we are is rarely good enough. We must constantly strive to grow. Growth and progress are the two primary imperatives within psychology. Consequently, discontent is built into the way we approach our psychological lives. The focus settles on what we don’t have, what we haven’t achieved, the progress we haven’t made.

Soul, on the other hand, values repetition. Repetition is a form of sustained attention, returning us repeatedly to a place, a person, or a practice, that engenders depth and familiarity. It is in the very essence of repetition that we come to know something more intimately, whether a partner, a friend, or our own interior worlds. Any movement toward depth requires repeated contact. Gary Snyder, Zen poet and nature philosopher, wrote that “Getting intimate with nature and our own wild natures is a matter of going face to face many times.” There is no depth without excavating and digging into the marrow of what matters to soul and culture. Repetition is a form of courtship.

Soul engages repetition in many ways. Consider how often we are brought back to the cave of our wounds. We are taken to these places, often unwillingly, as a way of remaining close-by, not straying too far from something essential in the making of soul. It is through the ongoing entanglement with our suffering, that flavor and shape are delivered into our lives. James Hillman says our wounds and traumas are “salt mines from which we gain a precious essence and without which the soul cannot live.”

Our sense of discontent, in part, arises out of neglecting the core practices that were repeated unbroken for hundreds of generations. Now, under the fevered pitch of individualism and the heroic ego, the original practices that wove the individual and the community together, have been largely forgotten. Consequently, the ritual of life is reduced into the routine of existence. That is repetition without soul. That is the drone of addiction. That is repetition that deadens.

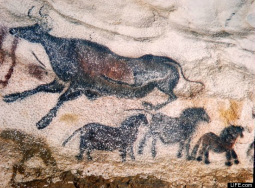

Soulful repetition offers a way to foster the art of remembering. We live in a culture that encourages amnesia and anesthesia; we forget, and we go numb. In our obsession with progress, the roots of memory have deteriorated and faded. “Repetition,” says anthropologist Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, “is a form of permanence.” This was vital for our survival. The dances, rituals, songs and stories, the intricate knowledge of plants and animals, how to shape adult human beings, all combined to form a means of maintaining the trail through the world. The continuity of wisdom passed on generation to generation was crucial to our ongoing survival. When we forget the old ways of our ancestors, we lose contact with the roots of wisdom.

We live in an ongoing tension between forgetting and remembering. Nearly all enduring cultures developed practices designed to help us remember three central things: who we are, where we belong, and what is sacred. Prayer, meditation, and ritual, are, at root, designed to help us stay awake. These practices serve to sustain the ground of remembrance, which is, in turn, a form of permanence.

Soul exerts its gravitational pull repeatedly in our lifetime, calling us into the rich loam of image, emotion, memory, dream and longing. Living cultures exert a similar compelling quality, drawing the community together through the repetitive gestures of ritual, initiatory cycles, pilgrimages to sacred places and the ongoing rounds of tending the village. Oral traditions are rooted in the rhythms of repetition. The great stories were told over and over again. It was in the retelling that the multiple layers hidden in the tale were slowly revealed. Our earliest shared acts were designed to weave and knit the community together, and then by extension, into the surrounding field of nature and cosmos. Repetition serves to continuously renew and reaffirm the entangled nature of our beings.

Soulful repetition is not boring or bland. It is musical, rhythmic, and enduring. We require touchstones of return to stay connected to what matters to soul and culture. Ultimately, repetition is a gesture of affection, of fidelity. We return again and again to tend what it is we love and by so doing, we keep it alive and vital.

Practice/Reflection: In what ways do you nourish the ritual of everyday life? What core practices help sustain your intimacy with soul? In what ways do you engage in repetition without soul?

We struggle with the idea of repetition, anything that seems too familiar in this culture. We want things to be novel, new and improved, the latest. There’s nothing wrong with this. It does, however, tinge the old and traditional with a feeling of being antiquated and outdated. (It’s interesting to note that to many traditional people, anything new was approached with an attitude of suspicion. Where did this come from? Will it serve the people? How will it affect the land?)

We live in a society that prizes constant innovation and novelty. The singular focus on growth and development has provided us with many new devices and technologies, and granted us a degree of ease seldom known by our ancestors. It also casts a long and weighty shadow. Embedded in this ideology is an obsession with progress.

Progress is holy scripture in this culture. It is the one-directional arrow of time and productivity that surrounds us and informs us daily. We feel it in the constant pressure to have more, be more, achieve more. There is something inherent in the concept of progress, however, that leaves a residue of discontent in its wake. The better life is always just beyond the horizon, awaiting the arrival of the latest product, accomplishment or discovery. We are taught to crave what’s next, the up and coming. The old and familiar are considered outworn and outdated. We are quick to discard anything considered old—including people—leaving us skimming the surface carried along on the swift moving current of progress.

This pressure is felt in our psychological lives as well. There is an ongoing focus on improving and being better. How we are is rarely good enough. We must constantly strive to grow. Growth and progress are the two primary imperatives within psychology. Consequently, discontent is built into the way we approach our psychological lives. The focus settles on what we don’t have, what we haven’t achieved, the progress we haven’t made.

Soul, on the other hand, values repetition. Repetition is a form of sustained attention, returning us repeatedly to a place, a person, or a practice, that engenders depth and familiarity. It is in the very essence of repetition that we come to know something more intimately, whether a partner, a friend, or our own interior worlds. Any movement toward depth requires repeated contact. Gary Snyder, Zen poet and nature philosopher, wrote that “Getting intimate with nature and our own wild natures is a matter of going face to face many times.” There is no depth without excavating and digging into the marrow of what matters to soul and culture. Repetition is a form of courtship.

Soul engages repetition in many ways. Consider how often we are brought back to the cave of our wounds. We are taken to these places, often unwillingly, as a way of remaining close-by, not straying too far from something essential in the making of soul. It is through the ongoing entanglement with our suffering, that flavor and shape are delivered into our lives. James Hillman says our wounds and traumas are “salt mines from which we gain a precious essence and without which the soul cannot live.”

Our sense of discontent, in part, arises out of neglecting the core practices that were repeated unbroken for hundreds of generations. Now, under the fevered pitch of individualism and the heroic ego, the original practices that wove the individual and the community together, have been largely forgotten. Consequently, the ritual of life is reduced into the routine of existence. That is repetition without soul. That is the drone of addiction. That is repetition that deadens.

Soulful repetition offers a way to foster the art of remembering. We live in a culture that encourages amnesia and anesthesia; we forget, and we go numb. In our obsession with progress, the roots of memory have deteriorated and faded. “Repetition,” says anthropologist Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, “is a form of permanence.” This was vital for our survival. The dances, rituals, songs and stories, the intricate knowledge of plants and animals, how to shape adult human beings, all combined to form a means of maintaining the trail through the world. The continuity of wisdom passed on generation to generation was crucial to our ongoing survival. When we forget the old ways of our ancestors, we lose contact with the roots of wisdom.

We live in an ongoing tension between forgetting and remembering. Nearly all enduring cultures developed practices designed to help us remember three central things: who we are, where we belong, and what is sacred. Prayer, meditation, and ritual, are, at root, designed to help us stay awake. These practices serve to sustain the ground of remembrance, which is, in turn, a form of permanence.

Soul exerts its gravitational pull repeatedly in our lifetime, calling us into the rich loam of image, emotion, memory, dream and longing. Living cultures exert a similar compelling quality, drawing the community together through the repetitive gestures of ritual, initiatory cycles, pilgrimages to sacred places and the ongoing rounds of tending the village. Oral traditions are rooted in the rhythms of repetition. The great stories were told over and over again. It was in the retelling that the multiple layers hidden in the tale were slowly revealed. Our earliest shared acts were designed to weave and knit the community together, and then by extension, into the surrounding field of nature and cosmos. Repetition serves to continuously renew and reaffirm the entangled nature of our beings.

Soulful repetition is not boring or bland. It is musical, rhythmic, and enduring. We require touchstones of return to stay connected to what matters to soul and culture. Ultimately, repetition is a gesture of affection, of fidelity. We return again and again to tend what it is we love and by so doing, we keep it alive and vital.

Practice/Reflection: In what ways do you nourish the ritual of everyday life? What core practices help sustain your intimacy with soul? In what ways do you engage in repetition without soul?

Gratitude For All That Is ©Francis Weller

There is a tradition among the native people of the Iroquois nation that goes back over a thousand years. It is known as the Thanksgiving Address. In the language of their people it is called, "Oh'nton Karihwat'hkwen," which translates, "Words Before All Else." The tradition involves the invocation of creation in a manner that extends thankfulness to all living things for their gifts to us. In this way, the people are brought into alignment with Nature. This eloquent ritual practice places gratitude as the beginning point for any further matters. Words Before All Else. What if our daily practice was to include this deep-seated reverence for creation and to acknowledge the never-ending flow of blessings that come our way? I remember Brother David Steindl-Rast saying, "It is not happiness that makes gratefulness, but gratefulness that makes happiness."

Gratitude is a central value to the indigenous soul. It forms the very heart of a life rooted in the awareness and recognition that we truly live in a gifting cosmos. Our deep time ancestors, and those remaining indigenous cultures still living in the old ways, know that everything we need has been given to us. In the ecology of the sacred our responsibility is to receive these blessings with gratitude. After all, what is the proper response to a gift if not gratitude? This understanding formed the basic attitude of traditional people and it is also readily recognized when we too, turn our attention to this fundamental truth.

Gratitude furthers the soul, calls it forth into the world in an act of intimacy. The simple gesture of receptivity paired with the expression of thankfulness completes the arc that binds the soul and world together in communion. Doing so confirms our relatedness with the cosmos and it is relationship that we are so in need of today. Our isolation and loneliness are in great part the consequence of forgetting to say thank you. This may sound simplistic, but the opposite is true. We live in a completely interdependent world and gratitude is the acknowledgement of this fundamental reality.

There is an old thought that says the strength of a community is reflected in the presence of generosity. In other words, the richness of the village is made visible by the expression of appreciation, recognition and thankfulness for the ways the people support one another and the way the world holds the people together. It seems that we are bereft of such a unifying ingredient at this time. Rather than acknowledging the multiple layers of gifting that are offered to us, we focus more on lack, on what is missing. This isn't some cynical move but rather a consequence of conditioning that continually references us back to what it is we don't have. Modernity keeps us hungry for more by turning our gaze towards absence. Psychology colludes in this as well by focusing primarily on what's wrong, what we didn't get in childhood, and so on. This chronic feeling of not enough makes it difficult to register blessings and to feel gratitude. It is our task to stay aware of what is being gifted here and now and to register the primary satisfactions that enrich our soul life, our emotional and bodily life. These are what make the moment thick with meaning and contentment: we have enough.

Gratitude is a spiritual responsibility. A grateful heart acknowledges and participates in the ongoing exchange with life. Gratitude is an act of faith, of trust in the ways of life. It is a confirmation that we are inextricably bound to each other thing in the cosmos. In this sense it is a reflection of belonging. Another thought of Br. David's was that we can feel either grateful or alienated, but never both at the same time. Gratefulness softens our sense of alienation. Our belonging is celebrated in thanksgiving, in full appreciation that we are both giver and receiver in the exchange of blessings.

How do we develop gratitude? Perhaps the most fundamental practice is listening. This attentive move slows us down to the speed of life where we are more resonant with the movements of the world. By listening we can register in our bodies just how fluid this flow of blessing is in our lives. Think about that. The constancy of the sun, moon, and stars, the generosity of the rains, rivers, the earth, the abundant richness of birdsong, the fragrance of roses, wet streets after a downpour, the delectable sweetness of blackberries warm with the heat of the day, the luscious colors of fall, all are offered to us freely. When we listen and take in the astonishingly sensuous earth, we come awake to the thunderous beauty that surrounds us. We are literally inundated with the world pouring through every opening and in this awareness, we recognize a fundamental truth: we are of the earth. In fact, as cosmologist Brian Swimme suggests, humans were put on earth to gawk. That is our cosmological destiny! To be astonished, amazed, delighted in the intricate weavings of the cosmos is to listen fully and to send out our sigh of appreciation is what is asked in return.

A second means by which we develop gratitude is through ritual. Ritual is the pitch through which our personal and collective voices are extended to the unseen dimensions of life, beyond the point of our minds and into the realms of nature and spirit. There are many opportunities for daily rituals that can drop us into a felt connection with life. Every meal we eat is a cosmological event. Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us that through the practice of mindfulness we become aware of the deep story within every meal. We are wedded to the cycles of sunshine and rain, the movements of microbes and root systems, the farmer and butcher, the animals and plants, the grocery store clerk. The entire cycle that brings the morsel to our mouths is what we are ingesting and to behold that movement with gratitude is to sacralize the moment.

Our annual Gratitude For All That Is ritual is a beautiful gesture to the visible and invisible worlds. To communally send our prayers of thanksgiving into the world is a rich and verdant act. Our ritual is eloquent and simple. After building a gratitude shrine, we make our prayers and offer small gifts to the other world of tobacco, corn meal, agates, or whatever has been brought. These offerings are made in a small crawl-in grotto made of fir boughs and ferns where they are left over night. In the morning, some children are asked to gather the offerings together and we then make our way singing across the grounds into the woods where a small opening is waiting to receive the gifts. At that time, the children that are there come forward and place handfuls of the offerings into the Mother's body and for that moment we are aligned with the rightness of our lives and the community. We have placed something back into her body in an act of recognition that everything we have, comes from her. It is sweet medicine.

Gratitude is the other hand of grief. It is the mature person who welcomes both. To deny either reality is to slip into chronic depression or to live in a superficial reality. Together they form a prayer that makes tangible the exquisite richness of life in this moment. Life is hard and filled with suffering. Life is also a most precious gift, a reason for continual celebration and appreciation. To everything, as the old prophet said, there is a season. This is the time of Thanksgiving.

Gratitude is a central value to the indigenous soul. It forms the very heart of a life rooted in the awareness and recognition that we truly live in a gifting cosmos. Our deep time ancestors, and those remaining indigenous cultures still living in the old ways, know that everything we need has been given to us. In the ecology of the sacred our responsibility is to receive these blessings with gratitude. After all, what is the proper response to a gift if not gratitude? This understanding formed the basic attitude of traditional people and it is also readily recognized when we too, turn our attention to this fundamental truth.

Gratitude furthers the soul, calls it forth into the world in an act of intimacy. The simple gesture of receptivity paired with the expression of thankfulness completes the arc that binds the soul and world together in communion. Doing so confirms our relatedness with the cosmos and it is relationship that we are so in need of today. Our isolation and loneliness are in great part the consequence of forgetting to say thank you. This may sound simplistic, but the opposite is true. We live in a completely interdependent world and gratitude is the acknowledgement of this fundamental reality.

There is an old thought that says the strength of a community is reflected in the presence of generosity. In other words, the richness of the village is made visible by the expression of appreciation, recognition and thankfulness for the ways the people support one another and the way the world holds the people together. It seems that we are bereft of such a unifying ingredient at this time. Rather than acknowledging the multiple layers of gifting that are offered to us, we focus more on lack, on what is missing. This isn't some cynical move but rather a consequence of conditioning that continually references us back to what it is we don't have. Modernity keeps us hungry for more by turning our gaze towards absence. Psychology colludes in this as well by focusing primarily on what's wrong, what we didn't get in childhood, and so on. This chronic feeling of not enough makes it difficult to register blessings and to feel gratitude. It is our task to stay aware of what is being gifted here and now and to register the primary satisfactions that enrich our soul life, our emotional and bodily life. These are what make the moment thick with meaning and contentment: we have enough.

Gratitude is a spiritual responsibility. A grateful heart acknowledges and participates in the ongoing exchange with life. Gratitude is an act of faith, of trust in the ways of life. It is a confirmation that we are inextricably bound to each other thing in the cosmos. In this sense it is a reflection of belonging. Another thought of Br. David's was that we can feel either grateful or alienated, but never both at the same time. Gratefulness softens our sense of alienation. Our belonging is celebrated in thanksgiving, in full appreciation that we are both giver and receiver in the exchange of blessings.

How do we develop gratitude? Perhaps the most fundamental practice is listening. This attentive move slows us down to the speed of life where we are more resonant with the movements of the world. By listening we can register in our bodies just how fluid this flow of blessing is in our lives. Think about that. The constancy of the sun, moon, and stars, the generosity of the rains, rivers, the earth, the abundant richness of birdsong, the fragrance of roses, wet streets after a downpour, the delectable sweetness of blackberries warm with the heat of the day, the luscious colors of fall, all are offered to us freely. When we listen and take in the astonishingly sensuous earth, we come awake to the thunderous beauty that surrounds us. We are literally inundated with the world pouring through every opening and in this awareness, we recognize a fundamental truth: we are of the earth. In fact, as cosmologist Brian Swimme suggests, humans were put on earth to gawk. That is our cosmological destiny! To be astonished, amazed, delighted in the intricate weavings of the cosmos is to listen fully and to send out our sigh of appreciation is what is asked in return.

A second means by which we develop gratitude is through ritual. Ritual is the pitch through which our personal and collective voices are extended to the unseen dimensions of life, beyond the point of our minds and into the realms of nature and spirit. There are many opportunities for daily rituals that can drop us into a felt connection with life. Every meal we eat is a cosmological event. Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us that through the practice of mindfulness we become aware of the deep story within every meal. We are wedded to the cycles of sunshine and rain, the movements of microbes and root systems, the farmer and butcher, the animals and plants, the grocery store clerk. The entire cycle that brings the morsel to our mouths is what we are ingesting and to behold that movement with gratitude is to sacralize the moment.

Our annual Gratitude For All That Is ritual is a beautiful gesture to the visible and invisible worlds. To communally send our prayers of thanksgiving into the world is a rich and verdant act. Our ritual is eloquent and simple. After building a gratitude shrine, we make our prayers and offer small gifts to the other world of tobacco, corn meal, agates, or whatever has been brought. These offerings are made in a small crawl-in grotto made of fir boughs and ferns where they are left over night. In the morning, some children are asked to gather the offerings together and we then make our way singing across the grounds into the woods where a small opening is waiting to receive the gifts. At that time, the children that are there come forward and place handfuls of the offerings into the Mother's body and for that moment we are aligned with the rightness of our lives and the community. We have placed something back into her body in an act of recognition that everything we have, comes from her. It is sweet medicine.

Gratitude is the other hand of grief. It is the mature person who welcomes both. To deny either reality is to slip into chronic depression or to live in a superficial reality. Together they form a prayer that makes tangible the exquisite richness of life in this moment. Life is hard and filled with suffering. Life is also a most precious gift, a reason for continual celebration and appreciation. To everything, as the old prophet said, there is a season. This is the time of Thanksgiving.

An Apprenticeship with Sorrow ©Francis Weller

“This night will pass, then we have work to do.”

- Rumi

Grief and loss touch us all, arriving at our door in many ways. They come swirling on the winds of divorce, tucked into the news of the death of someone dear, as an illness that alters the course of a life. For many of us, grief is tied intimately to the ravages we witness daily to watersheds and forests, the extinction of species, the collapse of democracy and the fading of civilization. Left unattended, these sorrows darken our days. It is our unexpressed sorrows, the congested stories of loss that, when left untouched, block our access to the vitality of the soul. To freely move in and out of the soul’s inner chambers, we must first clear the way. This requires finding meaningful ways to speak of sorrow. This requires an apprenticeship with sorrow. Learning to welcome, hold and metabolize sorrow is the work of a lifetime.

Our apprenticeship begins as we come to understand that grief is ever-present in our lives. This is a difficult realization, but one that carries the opportunity of opening our heart to a deeper love for our singular life and for the wind-swept world of which we are a part. We begin by simply picking up the shards of grief that lie littered on the floor of our house. Nothing special. Nothing heroic. Not unlike young novices entering an apprenticeship with the master teacher, we begin humbly—sweeping the shavings, mixing the pigments, cleaning the brushes, tending the fires. We begin the process by building our capacity to hold sorrow in the womb of the heart. Through this practice, we become able to welcome the pervasive and encompassing presence of grief.

-

Grief works us in profound ways, reshaping us moment by moment in the heat of loss.

We are also asked to work grief and to take up our apprenticeship with fidelity and love.

-

Tremendous psychic strength is required to engage the wild images, searing emotions, chaotic dreams, grief-stained memories, and visceral sensations that arise in times of deep grief. We must build soul muscle to meet these times with anything resembling affection. The apprenticeship is long.

Grief is more than an emotion; it is also a faculty of being human. Grieving is a skill that must be developed or we will find ourselves migrating to the margins of our lives in hope of avoiding the inevitable entanglements with loss. It is through the rites of grieving that we are ripened as human beings. Grief invites gravity and depth into our world. We possess the profound capacity to metabolize sorrow into something medicinal for our soul and the soul of the community. The skill of grieving well enables us to become current—to live in the present moment and feel the electricity of life. We gradually turn our attention to what is here, now, and less to our need to repair history. We remember we are more verb than noun, more a jumpy rhythm, a wild song, a fluid leap than a fixed thing in space. As Spanish poet Jaime Gil de Biedma said, “I believed I wanted to be a poet, but deep down I just wanted to be a poem.”

-

This apprenticeship is, at heart, about the shaping of elders, the ones capable of meeting

the pain and suffering of the world with a dignified and robust bearing.

-

After years of walking alongside grief, working with its difficult cargo, we gradually come to see how we have been reshaped by this companionship. We see how we have cultivated a greater interior space to hold more of what life brings to us. What slowly emerges from this long apprenticeship, this vigil with sorrow, is a spaciousness capable of holding it all—the beauty and the loss, the despair and the yearning, the fear and the love. We become immense: the apprenticeship patiently crafts an elder.

After years of holding steady with sorrow, a distillation of wisdom occurs. We develop a capacity to see in the darkness and find there, in the depths of it all, something holy, something eternal. We touch the indwelling sacredness of the life we inhabit, digesting bitterness and returning* with a determination to feed the community. We become a hive of imagination, dispensing what we have gathered over this extended education of the heart. What was learned was not meant for us alone, but was meant to be tossed like seed into a fertile mind, a waiting community, a hungry culture.

Elders are a composite of contradictions: fierce and forgiving, joyful and melancholy, intense and spacious, solitary and communal. They have been seasoned by a long fidelity to love and loss. We become elders by accepting life on life’s terms, gradually relinquishing the fight to have it fit our expectations. Elders have no quarrel with the ways of the world. Initiated through many years of loss, they have come to know that life is hard, riddled with failures, betrayals and deaths. They have made peace with the imperfections inherent in life. The wounds and losses they encounter become the material with which to shape a life of meaning, humor, joy, depth, and beauty. They do not push away suffering, nor wish to be exempt from the inevitable losses that come. They know the futility of such a wish. This acceptance frees them to radically receive the stunning elegance of the world.

Ultimately, each elder is a storehouse of living memory, a carrier of wisdom. Theirs are the voices that rise on behalf of the commons, at times fiery, at times beseeching. They live outside culture yet are its greatest protectors, becoming wily dispensers of love and blessings. They offer a resounding “Yes” to the generations that follow. That is their legacy and gift.

When the season is right, when we have been tempered sufficiently by the heat of life, we are asked to take up the mantle of elderhood as the most ordinary of things. Nothing special about it. It is ordinary to know loss and sorrow, to be pulled below the surface of life and be reshaped by the currents of grief. It is ordinary to be deepened by the draw of sorrow and its intense wash, clearing away old debris and outdated strategies. It is ordinary to feel the aperture of the heart open because of our intimacy with grief. No longer blinded by the allure of being special, we are free to take our place in the world, casting blessings by the simple offer of our presence, seasoned by sorrow.

-

This is how elders are crafted: tempered between the heat of loss and the weight of loving this world.

-

We are all preparing for our own disappearance, our one last breath. It is difficult to pick up this thread and hold it in our hand. Each of us is fated to leave this shining world, to slip off this elegant coat of skin, to release our stories to the wind and return our bones to the earth. Saying goodbye, however, is not easy or something we give much thought to in our daily lives.

How do we say goodbye? How do we acknowledge all that has held beauty and value in our lives—those we love, those who touched our lives with kindness, those whose shelter allowed us to extend ourselves into the world? How do we let go of sunsets and making love, of pomegranates and walks on the bluff? Yet, we must. We must release the entire fantastic world with one last breath. We will all fall into the mystery. We are most alive at the threshold of loss and revelation.

- Rumi

Grief and loss touch us all, arriving at our door in many ways. They come swirling on the winds of divorce, tucked into the news of the death of someone dear, as an illness that alters the course of a life. For many of us, grief is tied intimately to the ravages we witness daily to watersheds and forests, the extinction of species, the collapse of democracy and the fading of civilization. Left unattended, these sorrows darken our days. It is our unexpressed sorrows, the congested stories of loss that, when left untouched, block our access to the vitality of the soul. To freely move in and out of the soul’s inner chambers, we must first clear the way. This requires finding meaningful ways to speak of sorrow. This requires an apprenticeship with sorrow. Learning to welcome, hold and metabolize sorrow is the work of a lifetime.

Our apprenticeship begins as we come to understand that grief is ever-present in our lives. This is a difficult realization, but one that carries the opportunity of opening our heart to a deeper love for our singular life and for the wind-swept world of which we are a part. We begin by simply picking up the shards of grief that lie littered on the floor of our house. Nothing special. Nothing heroic. Not unlike young novices entering an apprenticeship with the master teacher, we begin humbly—sweeping the shavings, mixing the pigments, cleaning the brushes, tending the fires. We begin the process by building our capacity to hold sorrow in the womb of the heart. Through this practice, we become able to welcome the pervasive and encompassing presence of grief.

-

Grief works us in profound ways, reshaping us moment by moment in the heat of loss.

We are also asked to work grief and to take up our apprenticeship with fidelity and love.

-

Tremendous psychic strength is required to engage the wild images, searing emotions, chaotic dreams, grief-stained memories, and visceral sensations that arise in times of deep grief. We must build soul muscle to meet these times with anything resembling affection. The apprenticeship is long.

Grief is more than an emotion; it is also a faculty of being human. Grieving is a skill that must be developed or we will find ourselves migrating to the margins of our lives in hope of avoiding the inevitable entanglements with loss. It is through the rites of grieving that we are ripened as human beings. Grief invites gravity and depth into our world. We possess the profound capacity to metabolize sorrow into something medicinal for our soul and the soul of the community. The skill of grieving well enables us to become current—to live in the present moment and feel the electricity of life. We gradually turn our attention to what is here, now, and less to our need to repair history. We remember we are more verb than noun, more a jumpy rhythm, a wild song, a fluid leap than a fixed thing in space. As Spanish poet Jaime Gil de Biedma said, “I believed I wanted to be a poet, but deep down I just wanted to be a poem.”

-

This apprenticeship is, at heart, about the shaping of elders, the ones capable of meeting

the pain and suffering of the world with a dignified and robust bearing.

-

After years of walking alongside grief, working with its difficult cargo, we gradually come to see how we have been reshaped by this companionship. We see how we have cultivated a greater interior space to hold more of what life brings to us. What slowly emerges from this long apprenticeship, this vigil with sorrow, is a spaciousness capable of holding it all—the beauty and the loss, the despair and the yearning, the fear and the love. We become immense: the apprenticeship patiently crafts an elder.

After years of holding steady with sorrow, a distillation of wisdom occurs. We develop a capacity to see in the darkness and find there, in the depths of it all, something holy, something eternal. We touch the indwelling sacredness of the life we inhabit, digesting bitterness and returning* with a determination to feed the community. We become a hive of imagination, dispensing what we have gathered over this extended education of the heart. What was learned was not meant for us alone, but was meant to be tossed like seed into a fertile mind, a waiting community, a hungry culture.

Elders are a composite of contradictions: fierce and forgiving, joyful and melancholy, intense and spacious, solitary and communal. They have been seasoned by a long fidelity to love and loss. We become elders by accepting life on life’s terms, gradually relinquishing the fight to have it fit our expectations. Elders have no quarrel with the ways of the world. Initiated through many years of loss, they have come to know that life is hard, riddled with failures, betrayals and deaths. They have made peace with the imperfections inherent in life. The wounds and losses they encounter become the material with which to shape a life of meaning, humor, joy, depth, and beauty. They do not push away suffering, nor wish to be exempt from the inevitable losses that come. They know the futility of such a wish. This acceptance frees them to radically receive the stunning elegance of the world.

Ultimately, each elder is a storehouse of living memory, a carrier of wisdom. Theirs are the voices that rise on behalf of the commons, at times fiery, at times beseeching. They live outside culture yet are its greatest protectors, becoming wily dispensers of love and blessings. They offer a resounding “Yes” to the generations that follow. That is their legacy and gift.

When the season is right, when we have been tempered sufficiently by the heat of life, we are asked to take up the mantle of elderhood as the most ordinary of things. Nothing special about it. It is ordinary to know loss and sorrow, to be pulled below the surface of life and be reshaped by the currents of grief. It is ordinary to be deepened by the draw of sorrow and its intense wash, clearing away old debris and outdated strategies. It is ordinary to feel the aperture of the heart open because of our intimacy with grief. No longer blinded by the allure of being special, we are free to take our place in the world, casting blessings by the simple offer of our presence, seasoned by sorrow.

-

This is how elders are crafted: tempered between the heat of loss and the weight of loving this world.

-

We are all preparing for our own disappearance, our one last breath. It is difficult to pick up this thread and hold it in our hand. Each of us is fated to leave this shining world, to slip off this elegant coat of skin, to release our stories to the wind and return our bones to the earth. Saying goodbye, however, is not easy or something we give much thought to in our daily lives.

How do we say goodbye? How do we acknowledge all that has held beauty and value in our lives—those we love, those who touched our lives with kindness, those whose shelter allowed us to extend ourselves into the world? How do we let go of sunsets and making love, of pomegranates and walks on the bluff? Yet, we must. We must release the entire fantastic world with one last breath. We will all fall into the mystery. We are most alive at the threshold of loss and revelation.

The Values of Soul: The Gifts of Restraint ©Francis Weller

In a series of talks I offered in early 2018, called Living a Soulful Life and Why It Matters, I shared multiple ways to see the daily manifestations of soul, how it reveals itself through our encounters with wounds, images, creativity, friendship, grief, the ancestors and more. Underlying these epiphanic displays are the values that soul holds, values that were shaped over thousands of years and which emerged as central to our survival as a species. In these times of disorientation and uncertainty, recovering these essential nodes of being may help us navigate the coming challenges in a more considered way.

We begin our exploration of the values of soul in a somewhat unexpected territory: restraint. The choice is intentional. In an age of instant gratification and excessive consumption, the value of restraint must come acutely into view. We are drowning in our possessions and our garbage. We are exhausting the very fabric of the world, consuming the equivalent of 1.7 earths every year. The depletion process is far outstripping the regeneration capacities of the planet. Restraint, however, is one of the least developed soul values we have. It may not be as sexy as courage and boldness. Nor is it the most popular at the party. Exuberance and abundance get that award. Restraint is more introspective, contained, held back. It is a bit austere, preferring not doing to doing.

There are both internal and external forms of restraint.

Internally, restraint invites a pause, a breath, a moment of reflection. How rarely we do this—pause, breathe, reflect. It is a core practice in the art of ripening. We must grant time and space for things to ripen and mature. Insights, intuitions, encounters, dreams, all require time to incubate and consolidate into something substantial. We continually reveal and share things too soon, rarely allowing a new revelation time to mature and become part of our psychic ground. We need to hold, contain, cook the material before sharing it with the world. It must be allowed to go through its own process of distillation prior to being revealed to questioning eyes. The value of restraint acknowledges this truth and creates a space where something can take shape according to its nature.

Our constant management and manipulation of all things psychic, reveals a lack of faith in the movements of soul. It is essential to practice non-interference, letting the deep work of soul go on without our interventions. As the great German mystic, Meister Eckhart said, “We must let go and let God.” Or as Jung said, paraphrasing Eckhart, “We must let go and let be.” Restraint is a form of trust in the deep workings of soul.

When we honor the value of restraint, the door to genuine receiving opens. Grasping to satisfy every hunger leaves no room for the generosity of the world to find us. Restraint is a form of faithfulness: faith that we will be cared for; that we will be offered kindness and care from others when our hearts and souls are troubled. Restraint opens the aperture where we can be found.

There is a marvelous tempering of psyche by the heat generated through non-action. It is a via negativa; a path of negation. To restrain means “to bind back” and “to hold back.” This creates heat through the tension of resistance. It is this heat that creates contour and shape to our interior lives. You can feel it when you hesitate to act on some impulse, desire or craving. Space is created when we let go of something. It requires strength and fortitude, commitment and devotion. It is a move toward holding steady, allowing the deeper and often hidden rhythms of soul to emerge.

The lyrical poet of Duende, Federico Garcia Lorca called us to live in the dynamic tension between discipline and passion. Restraint is a form of discipline. It offers a holding space, a vessel in the old Alchemical language, for cooking the raw material, the prima materia, into a new shape.

We place a great deal of emphasis on desire, longing, expression, and wildness in our lives. All of this is beautiful and necessary. Without its other side, however, we lack the tempering that is provided through the tension of restraint. It’s possible, that holding back is as necessary as action is to the soul.

Restraint offers a powerful antidote to our self-focused psychologies and our consumptive economics. It loosens the tight grip of the self as the sole signifier of importance. Through the agency of restraint, we can attend to the needs and voices of others, human and more-than-human, in our concerns. Many traditions practiced gestures of restraint, such as fasting, as a means of returning the individual, again and again, back to the ground of humility.

Externally, at the heart of restraint is an awareness that our well-being is entangled with all others. Many myths and fairy tales speak of the necessity of restraint, particularly in terms of our relations with our plant and animal kin. These wisdom tales warn of the dangers that accompany selfishness, greed, and taking more than necessary. To practice self-control is to maintain the tender equilibrium between the worlds. In many of these tales, the animals would withdraw their consent to be offered to the human world when we acted out of balance. Consequently, the game disappeared, and the people suffered. Their intuitive knowledge was meant to prevent wholesale depletion of what it was they required to survive. We have forgotten this life-preserving value in our times. Overfishing, mountain top removal, clear-cutting of forests, loss of topsoil, emptying and poisoning of aquifers, are all outgrowths of the failure to practice restraint.

Restraint moves contrary to the goals of acquisition and accumulation. It is, rather, a value that serves the commons, arising as it does, from our long story of mutual survival. It is rooted in an embedded truth that we have endured together. Our survival is possible only in collaboration with the many others with whom we share this stunning world.

The Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast territory of the continent practiced a principle of considering the 7th Generation in their deliberations. Any action they took, would have to be sustainable for those generations yet to come. This is the embodiment of cultural restraint.

There is a potent connection between restraint and humility. The action/non-action of restraint suggests that there is a value in holding back, of limiting the movements we are wanting to make. Restraint recognizes the dangers of continuous growth, addition, and consumption. It leans into the wisdom of moderation—another word not praised in our no-limits culture. In an age of “You can have it all,” there is an implicit entitlement to consume, extract and possess. What drives this rapacious appetite is an interior sense of emptiness and lack. We have forgotten the primary satisfactions* in our lives and have been left with a deep absence in our core.

Restraint, along with patience, offers a pause, a moment of reflection where we can take in the needs of another. In the space of holding back, we recognize that our well-being is intricately entwined with the health of the commons. To act in a selfish manner is to put our own lives in jeopardy. To take too much disturbs the delicate balance of watersheds and communities. Restraint asks us to cherish the fact of our mutually entangled lives. We are inseparable from all that surrounds us.

In the coming years, we will inevitably be required to reduce, not only our consumption, but also our sense of needing so much to live a rich and soulful life. Let us come to see the value of restraint, of creating space through the practice of not doing. It may be there that we find ourselves escorted into the chamber of what it is the soul truly longs for.

* Primary satisfactions are the undeniable and irrefutable needs of the psyche that were established over the long journey of our species and are imprinted in our beings as expectations awaiting fulfillment.

The primary satisfactions are the elemental constituents of a healthy psychic and physical life. These included matters such as: adequate and available touch; comfort in times of grief and pain; abundant play; the sharing of food eaten slowly; dark, starlit nights; the pleasures of friendship and laughter. They also are centered on a rich and responsive ritual life that addresses concerns central to our lives such as initiation, healing and other major transitions; continual exposure to and participation with nature; storytelling, dancing, and music; attentive and engaged elders; a system of inclusion based on equality and access to a varied and sensuous world.

We begin our exploration of the values of soul in a somewhat unexpected territory: restraint. The choice is intentional. In an age of instant gratification and excessive consumption, the value of restraint must come acutely into view. We are drowning in our possessions and our garbage. We are exhausting the very fabric of the world, consuming the equivalent of 1.7 earths every year. The depletion process is far outstripping the regeneration capacities of the planet. Restraint, however, is one of the least developed soul values we have. It may not be as sexy as courage and boldness. Nor is it the most popular at the party. Exuberance and abundance get that award. Restraint is more introspective, contained, held back. It is a bit austere, preferring not doing to doing.

There are both internal and external forms of restraint.

Internally, restraint invites a pause, a breath, a moment of reflection. How rarely we do this—pause, breathe, reflect. It is a core practice in the art of ripening. We must grant time and space for things to ripen and mature. Insights, intuitions, encounters, dreams, all require time to incubate and consolidate into something substantial. We continually reveal and share things too soon, rarely allowing a new revelation time to mature and become part of our psychic ground. We need to hold, contain, cook the material before sharing it with the world. It must be allowed to go through its own process of distillation prior to being revealed to questioning eyes. The value of restraint acknowledges this truth and creates a space where something can take shape according to its nature.

Our constant management and manipulation of all things psychic, reveals a lack of faith in the movements of soul. It is essential to practice non-interference, letting the deep work of soul go on without our interventions. As the great German mystic, Meister Eckhart said, “We must let go and let God.” Or as Jung said, paraphrasing Eckhart, “We must let go and let be.” Restraint is a form of trust in the deep workings of soul.

When we honor the value of restraint, the door to genuine receiving opens. Grasping to satisfy every hunger leaves no room for the generosity of the world to find us. Restraint is a form of faithfulness: faith that we will be cared for; that we will be offered kindness and care from others when our hearts and souls are troubled. Restraint opens the aperture where we can be found.

There is a marvelous tempering of psyche by the heat generated through non-action. It is a via negativa; a path of negation. To restrain means “to bind back” and “to hold back.” This creates heat through the tension of resistance. It is this heat that creates contour and shape to our interior lives. You can feel it when you hesitate to act on some impulse, desire or craving. Space is created when we let go of something. It requires strength and fortitude, commitment and devotion. It is a move toward holding steady, allowing the deeper and often hidden rhythms of soul to emerge.

The lyrical poet of Duende, Federico Garcia Lorca called us to live in the dynamic tension between discipline and passion. Restraint is a form of discipline. It offers a holding space, a vessel in the old Alchemical language, for cooking the raw material, the prima materia, into a new shape.

We place a great deal of emphasis on desire, longing, expression, and wildness in our lives. All of this is beautiful and necessary. Without its other side, however, we lack the tempering that is provided through the tension of restraint. It’s possible, that holding back is as necessary as action is to the soul.

Restraint offers a powerful antidote to our self-focused psychologies and our consumptive economics. It loosens the tight grip of the self as the sole signifier of importance. Through the agency of restraint, we can attend to the needs and voices of others, human and more-than-human, in our concerns. Many traditions practiced gestures of restraint, such as fasting, as a means of returning the individual, again and again, back to the ground of humility.

Externally, at the heart of restraint is an awareness that our well-being is entangled with all others. Many myths and fairy tales speak of the necessity of restraint, particularly in terms of our relations with our plant and animal kin. These wisdom tales warn of the dangers that accompany selfishness, greed, and taking more than necessary. To practice self-control is to maintain the tender equilibrium between the worlds. In many of these tales, the animals would withdraw their consent to be offered to the human world when we acted out of balance. Consequently, the game disappeared, and the people suffered. Their intuitive knowledge was meant to prevent wholesale depletion of what it was they required to survive. We have forgotten this life-preserving value in our times. Overfishing, mountain top removal, clear-cutting of forests, loss of topsoil, emptying and poisoning of aquifers, are all outgrowths of the failure to practice restraint.

Restraint moves contrary to the goals of acquisition and accumulation. It is, rather, a value that serves the commons, arising as it does, from our long story of mutual survival. It is rooted in an embedded truth that we have endured together. Our survival is possible only in collaboration with the many others with whom we share this stunning world.

The Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast territory of the continent practiced a principle of considering the 7th Generation in their deliberations. Any action they took, would have to be sustainable for those generations yet to come. This is the embodiment of cultural restraint.

There is a potent connection between restraint and humility. The action/non-action of restraint suggests that there is a value in holding back, of limiting the movements we are wanting to make. Restraint recognizes the dangers of continuous growth, addition, and consumption. It leans into the wisdom of moderation—another word not praised in our no-limits culture. In an age of “You can have it all,” there is an implicit entitlement to consume, extract and possess. What drives this rapacious appetite is an interior sense of emptiness and lack. We have forgotten the primary satisfactions* in our lives and have been left with a deep absence in our core.

Restraint, along with patience, offers a pause, a moment of reflection where we can take in the needs of another. In the space of holding back, we recognize that our well-being is intricately entwined with the health of the commons. To act in a selfish manner is to put our own lives in jeopardy. To take too much disturbs the delicate balance of watersheds and communities. Restraint asks us to cherish the fact of our mutually entangled lives. We are inseparable from all that surrounds us.

In the coming years, we will inevitably be required to reduce, not only our consumption, but also our sense of needing so much to live a rich and soulful life. Let us come to see the value of restraint, of creating space through the practice of not doing. It may be there that we find ourselves escorted into the chamber of what it is the soul truly longs for.

* Primary satisfactions are the undeniable and irrefutable needs of the psyche that were established over the long journey of our species and are imprinted in our beings as expectations awaiting fulfillment.

The primary satisfactions are the elemental constituents of a healthy psychic and physical life. These included matters such as: adequate and available touch; comfort in times of grief and pain; abundant play; the sharing of food eaten slowly; dark, starlit nights; the pleasures of friendship and laughter. They also are centered on a rich and responsive ritual life that addresses concerns central to our lives such as initiation, healing and other major transitions; continual exposure to and participation with nature; storytelling, dancing, and music; attentive and engaged elders; a system of inclusion based on equality and access to a varied and sensuous world.

Some People Wake Up: Reflections on Initiation ©Francis Weller

Again and again

Some people wake up.

They have no ground in the crowd

And they emerge according to broader laws.

They carry strange customs with them,

And demand room for bold gestures.

The future speaks ruthlessly through them.

-Rainer Maria Rilke

Dear friend. No doubt you have noticed that we are living in turbulent times culturally and as a planet. All pretense of immunity is collapsing as we realize how completely entangled our lives are with one another, with kelp beds and calving glaciers, with refugees and the dreams of young people everywhere. The disequilibrium shaking the world feels like a continual tremor on the fault lines of our psychic lives. Very few things feel stable. It is like a fever dream. It may be that this is the initiatory threshold we require to wake us up. Whatever is happening, much will be asked of us if we are to make it through the whitewater of this narrow passage. We do not know what lies ahead, but one thing is sure: This as a time for bold gestures. It is time to wake up and humbly take our place on this stunning planet. The future is speaking ruthlessly through us.

_________________________________________________________

The immediate need of our time is for ripened and seasoned adult human beings to take their place in our communities; individuals who carry a deep and abiding fidelity to the living body of this benevolent earth, to beauty and to their own souls. Traditionally, these were the ones who had successfully crossed a series of initiatory thresholds and had come through as protectors and carriers of the communal soul. They were the ones whose artistry and wisdom kept the current of culture alive. We live in a society that has all but abandoned rituals of initiation. Consequently, we are languishing from the absence of mature and robust adults.

How do we become seasoned adults, a true human being? This is not a given. Traditionally this was the work of culture. Through the long labors of multiple initiations, individuals were gradually crafted into persons of substance and gravity. The process yielded someone more attuned to responsibilities than rights, more aware of multiple entanglements than entitlements. They were initiated into a vast sea of intimacies; with the village, star clusters and gnarled old oaks, the pool of ancestors and the scented earth.

Through the sustained attention of culture, individuals were ripened

into adults capable of sustaining culture: A marvelous symmetry.

We are meant to cross many thresholds in our lifetime, each a further embodiment of the soul's innate character. Yet many of us carry the uncomfortable thought that we are unsure of our place in the world, still anxious about our sense of value and our right to be here. The unfinished business of adolescence haunts us and makes it hard to live into the larger arc of our lives.

Crossing the threshold from adolescence into adulthood requires an ordeal, a tempering of the individual that begins the process of ripening. There is no easy passage. Many traditional cultures escorted their youth into the world of adulthood and the sacred through an elaborate series of rituals. These rituals occurred in nature, in the holding space of forests and caves, savannas and bush. It was a space outside the ordinary world of the village, apart from the community and often took place over many weeks and even months. It was a time of tempering the young ones with intense ritual ordeals that took them beyond their capacities to endure. Something died in the process. Something needed to die in the process. And something needed to come forward. Some new shape of identity that was wedded to the silt and slope of the land, that spoke the feathered and furred language of the creatures and the song of the dawn. This new identity was co-mingled with the holy topography. They became one and the same.

Underneath and holding up this initiatory process was a deep and abiding relationship to the wild world and the spirits of place. This passage was rooted in a nearly endless succession of generations that had come to learn the necessity of such a transition. The awareness for this is essentially universal: our souls must be shaped by a process of intense ritual encounter, communal reflection, and immersion in the natural and supranatural worlds. In other words, to become an adult, certain gateways needed to be crossed for that territory to be fully embedded within the person.

What we witness daily in the litany of injustices and exploitation of others and the world are the actions of uninitiated individuals. It is not difficult to see how questions of adequacy and inclusion are often portrayed in gross exaggerations of power and force. Nor is it a stretch to see how the persistent hunger in the unripened psyche of so many is at the heart of our violent consumption of the planet.

Initiation is an entrance into a place, a terrain. It is a courtship of a large dreaming animal. It is not an abstract ideal of psychological accomplishment, but rather an entrance into the specificity of locale, of geography, of rhizomes and crab thought, mercurial imaginings, moon cycles, and seasonal rhythms, with eyes that regard these as sacred. Through these intimacies, a grand landscape comes into vision: a world riddled with spirit, ancestors, community, cosmos and the dreams of those yet to come.

Initiation, in its deepest traditional sense, was meant to keep the world alive. The purpose was not individual, but cosmological in scope. It was never for the individual. This is very hard for us to get our minds around, having been conditioned within a psychological tradition that fixates everything upon the “self.” It is always about me and my growth! Here’s the truth, however: Initiation was an act of sacrifice on behalf of the greater circle of life into which the initiate is brought and to which they now hold allegiance.

Can you feel your longing for just such a knowing?

At the same time, initiation profoundly affects us as individuals. It activates and authorizes the particular soul thread we came to offer the waiting world. Much like those seed pods that only germinate in the heat of fire, the soul seed we carry responds to the heat generated by initiation.

The soul is fully aware of the reciprocal relationship it has with the wild world, with the worlds of spirit and the ancestors. Soul recognizes the innate requirements for maintaining these connections. It was the role of mature individuals to honor our place in the family of things by carrying out the rituals of gratitude and renewal that sustain our relations with the breathing, animate world. Initiation embeds in us a fundamental requirement of being human:

We are meant to feed Life in an ongoing way!

As we mature, we are asked to come into a more reciprocal relationship with the earth. We are called to develop the manners which help sustain the body of this exquisite world. Values such as respect, restraint, (our least developed spiritual value) gratitude, and courage help to fortify our ability to stand and protect what we love. We are here to participate in the ongoing creation, to offer our imagination, affection, and devotion to the sustaining of the world.

It is not difficult to see how far we live as a culture from these practices. The central question is, how can we, once again, recognize the transforming cadence of initiation in a time of amnesia, a time in which the old forms have been abandoned?

The truth is initiation is not optional. Every one of us will be taken to the edge, pulled by the gravity of soul to engage the rigors of ripening us into something substantial. No one is exempt. Imagine if we could see the circumstances of our lives as the raw material necessary for the movement across the threshold into our adult lives. This could free us in radical ways. From a mythic perspective, these are the conditions that can cook the soul and bring us closer to the mystery of our own singular incarnation. The rough initiations of loss, trauma, defeats, betrayals, illness, become the Prima Materia, the beginning matter, for undertaking the crossing into our more encompassing life. So much depends upon how we perceive what it is that is happening in our world. Taking a mythic view enables us to see our circumstances as necessary, even required, for the work of deep change to take place.

The need is clear: we must cultivate a robust collective of adults whose primary fealty is to the life-giving world upon which we depend. We must be able to feel our loyalties to watersheds, migratory pathways, marginalized communities, and the soul of the world. We must feel the bedrock of our aliveness, and the reality of our wild and exuberant lives. Initiation tempers the soul, drawing out its hidden essence and calls forth the medicine we came to offer this stunning world. It is time to wake up!

Some people wake up.

They have no ground in the crowd

And they emerge according to broader laws.

They carry strange customs with them,

And demand room for bold gestures.

The future speaks ruthlessly through them.

-Rainer Maria Rilke

Dear friend. No doubt you have noticed that we are living in turbulent times culturally and as a planet. All pretense of immunity is collapsing as we realize how completely entangled our lives are with one another, with kelp beds and calving glaciers, with refugees and the dreams of young people everywhere. The disequilibrium shaking the world feels like a continual tremor on the fault lines of our psychic lives. Very few things feel stable. It is like a fever dream. It may be that this is the initiatory threshold we require to wake us up. Whatever is happening, much will be asked of us if we are to make it through the whitewater of this narrow passage. We do not know what lies ahead, but one thing is sure: This as a time for bold gestures. It is time to wake up and humbly take our place on this stunning planet. The future is speaking ruthlessly through us.

_________________________________________________________

The immediate need of our time is for ripened and seasoned adult human beings to take their place in our communities; individuals who carry a deep and abiding fidelity to the living body of this benevolent earth, to beauty and to their own souls. Traditionally, these were the ones who had successfully crossed a series of initiatory thresholds and had come through as protectors and carriers of the communal soul. They were the ones whose artistry and wisdom kept the current of culture alive. We live in a society that has all but abandoned rituals of initiation. Consequently, we are languishing from the absence of mature and robust adults.

How do we become seasoned adults, a true human being? This is not a given. Traditionally this was the work of culture. Through the long labors of multiple initiations, individuals were gradually crafted into persons of substance and gravity. The process yielded someone more attuned to responsibilities than rights, more aware of multiple entanglements than entitlements. They were initiated into a vast sea of intimacies; with the village, star clusters and gnarled old oaks, the pool of ancestors and the scented earth.

Through the sustained attention of culture, individuals were ripened

into adults capable of sustaining culture: A marvelous symmetry.

We are meant to cross many thresholds in our lifetime, each a further embodiment of the soul's innate character. Yet many of us carry the uncomfortable thought that we are unsure of our place in the world, still anxious about our sense of value and our right to be here. The unfinished business of adolescence haunts us and makes it hard to live into the larger arc of our lives.

Crossing the threshold from adolescence into adulthood requires an ordeal, a tempering of the individual that begins the process of ripening. There is no easy passage. Many traditional cultures escorted their youth into the world of adulthood and the sacred through an elaborate series of rituals. These rituals occurred in nature, in the holding space of forests and caves, savannas and bush. It was a space outside the ordinary world of the village, apart from the community and often took place over many weeks and even months. It was a time of tempering the young ones with intense ritual ordeals that took them beyond their capacities to endure. Something died in the process. Something needed to die in the process. And something needed to come forward. Some new shape of identity that was wedded to the silt and slope of the land, that spoke the feathered and furred language of the creatures and the song of the dawn. This new identity was co-mingled with the holy topography. They became one and the same.

Underneath and holding up this initiatory process was a deep and abiding relationship to the wild world and the spirits of place. This passage was rooted in a nearly endless succession of generations that had come to learn the necessity of such a transition. The awareness for this is essentially universal: our souls must be shaped by a process of intense ritual encounter, communal reflection, and immersion in the natural and supranatural worlds. In other words, to become an adult, certain gateways needed to be crossed for that territory to be fully embedded within the person.

What we witness daily in the litany of injustices and exploitation of others and the world are the actions of uninitiated individuals. It is not difficult to see how questions of adequacy and inclusion are often portrayed in gross exaggerations of power and force. Nor is it a stretch to see how the persistent hunger in the unripened psyche of so many is at the heart of our violent consumption of the planet.

Initiation is an entrance into a place, a terrain. It is a courtship of a large dreaming animal. It is not an abstract ideal of psychological accomplishment, but rather an entrance into the specificity of locale, of geography, of rhizomes and crab thought, mercurial imaginings, moon cycles, and seasonal rhythms, with eyes that regard these as sacred. Through these intimacies, a grand landscape comes into vision: a world riddled with spirit, ancestors, community, cosmos and the dreams of those yet to come.

Initiation, in its deepest traditional sense, was meant to keep the world alive. The purpose was not individual, but cosmological in scope. It was never for the individual. This is very hard for us to get our minds around, having been conditioned within a psychological tradition that fixates everything upon the “self.” It is always about me and my growth! Here’s the truth, however: Initiation was an act of sacrifice on behalf of the greater circle of life into which the initiate is brought and to which they now hold allegiance.

Can you feel your longing for just such a knowing?

At the same time, initiation profoundly affects us as individuals. It activates and authorizes the particular soul thread we came to offer the waiting world. Much like those seed pods that only germinate in the heat of fire, the soul seed we carry responds to the heat generated by initiation.

The soul is fully aware of the reciprocal relationship it has with the wild world, with the worlds of spirit and the ancestors. Soul recognizes the innate requirements for maintaining these connections. It was the role of mature individuals to honor our place in the family of things by carrying out the rituals of gratitude and renewal that sustain our relations with the breathing, animate world. Initiation embeds in us a fundamental requirement of being human:

We are meant to feed Life in an ongoing way!

As we mature, we are asked to come into a more reciprocal relationship with the earth. We are called to develop the manners which help sustain the body of this exquisite world. Values such as respect, restraint, (our least developed spiritual value) gratitude, and courage help to fortify our ability to stand and protect what we love. We are here to participate in the ongoing creation, to offer our imagination, affection, and devotion to the sustaining of the world.

It is not difficult to see how far we live as a culture from these practices. The central question is, how can we, once again, recognize the transforming cadence of initiation in a time of amnesia, a time in which the old forms have been abandoned?

The truth is initiation is not optional. Every one of us will be taken to the edge, pulled by the gravity of soul to engage the rigors of ripening us into something substantial. No one is exempt. Imagine if we could see the circumstances of our lives as the raw material necessary for the movement across the threshold into our adult lives. This could free us in radical ways. From a mythic perspective, these are the conditions that can cook the soul and bring us closer to the mystery of our own singular incarnation. The rough initiations of loss, trauma, defeats, betrayals, illness, become the Prima Materia, the beginning matter, for undertaking the crossing into our more encompassing life. So much depends upon how we perceive what it is that is happening in our world. Taking a mythic view enables us to see our circumstances as necessary, even required, for the work of deep change to take place.

The need is clear: we must cultivate a robust collective of adults whose primary fealty is to the life-giving world upon which we depend. We must be able to feel our loyalties to watersheds, migratory pathways, marginalized communities, and the soul of the world. We must feel the bedrock of our aliveness, and the reality of our wild and exuberant lives. Initiation tempers the soul, drawing out its hidden essence and calls forth the medicine we came to offer this stunning world. It is time to wake up!

BAPTIZED BY DARK WATERS ©Francis Weller

“I have faith in nights”

- Rainer Maria Rilke

There are times, more akin to seasons, when we are brought down into the terrain of shadows. These times are not caused by something happening in our day-lit world, nor by history or genetic inheritance. It seems we are required to periodically surrender and meander in the vast uncharted terrain of the underworld. These are times initiated by soul. Most of us will have times like this. They will descend upon us, as they say, “out of the blue.” In truth, it is more blue bending toward black.

In Alchemy, these seasonal migrations were called times in the Nigredo, or the Blackening. This is helpful to see that this as an inevitable and necessary time, a time of shedding and letting go, of sitting close to the furnace of death as it cooks away all that is spent and no longer serving life. Our time in the Nigredo is a period of dissolution. Old patterns and perceptions, old, outworn identities begin to dissolve as we are unmade. Things fall apart. There is an unraveling, an emptying of hope and an undermining of our great heroic enterprise to be in control and rise above our suffering. We are taken down to the ground and asked to “dance the wild dance of no hope!”

Anyone who has ever been escorted into the underworld, knows full well how uncharted this place feels. We are without fixed stars, known destinations, familiar markers or guideposts. The Nigredo was called the “subtle dissolver” in alchemy and was viewed as a necessary element in the great work of creating the philosopher’s stone. The work could only commence through the attainment of the Nigredo. Only when the familiar structures were eroded was it possible for something new to arise. It is difficult for us to see our time in the underworld as something required for the deepening of our soul life. One major challenge to this understanding is that we are highly conditioned to strive for the light, to rise above everything and overcome every obstacle. Not so when soul pulls us downward.

We meet a different self in this grotto of darkness, someone closer to the dream world and comfortable in shadowed places. This one knows about melancholy and hasn’t been swept up in the pursuit of the light. We need to know this other one who is more kindred with the nature of shimmering moonlight and soul than the brilliant sunlight of consciousness. This self sees through the layers of conditioning we all endure that oppress and domesticate. This one expresses something true and alive whether through the complex rhythms of the blues, in shades of nuanced speech or in the tender intimacy of vulnerability. This other is inclined to silence, the night sky, the poetry of Neruda and Machado and the friendship of solitude.

When we find ourselves walking through the ink-black night of the underworld, we quickly begin looking for the exit door. The old myths and the teachings of alchemy suggest we take a different direction. The work, they say, is to move closer to the heart of the darkness. The alchemists said it clearly; the work is to make the black, “blacker than black,” the “color of a raven’s head.”

Not exactly the news we were hoping for.